I built the installation DUNA | AИUꓷ in Štúrovo, Slovakia during my 2017 Bridge Guard artist residency. I used driftwood & antique pottery shards collected from the Danube (called Duna in Hungarian).

That spring I discovered a history still very much alive to the locals. Once a single community spanned the river, with daily cross traffic. Then politics and war pushed national borders back and forth five times within a hundred year span. During the Communist regime (1948-1989) the river served as a wall. The regime employed a heavy military presence and refused to repair the bridge destroyed by the Germans during World War II. Families were separated for years with no family visits and little mail. Older residents will still tell you about going to the river’s edge to call across, announcing births and deaths to their loved ones, the water carrying the sound. To this day a yearly festival features string musicians playing music on both sides, each side improvising as they respond to the slightly delayed music the water brings across to them.

When the EU rebuilt the Maria Valeria Bridge in 2001, the bridge had spent more years collapsed than connecting the two countries, Slovakia and Hungary. The purpose of the Bridge Guard residency is to use the arts to strengthen cultural ties, the lack of which leads to the kind of destruction and pain of isolation.

DUNA | AИUꓷ recasts the Danube as a uniting force pulling water, objects and people together instead of dividing them. Gravity inexorably pulls water and the things water carries towards the river-bed. Rivers spend years smoothing the surfaces, mixing, and tumbling. The process strips away nationality, leaving only the visible passage of time as evidence of the object’s story. Objects on a riverbank can’t tell you from which side of the river they originated. Every day the river arranges and rearranges its abundant offerings as a non-linear history, the past and present offered up together.

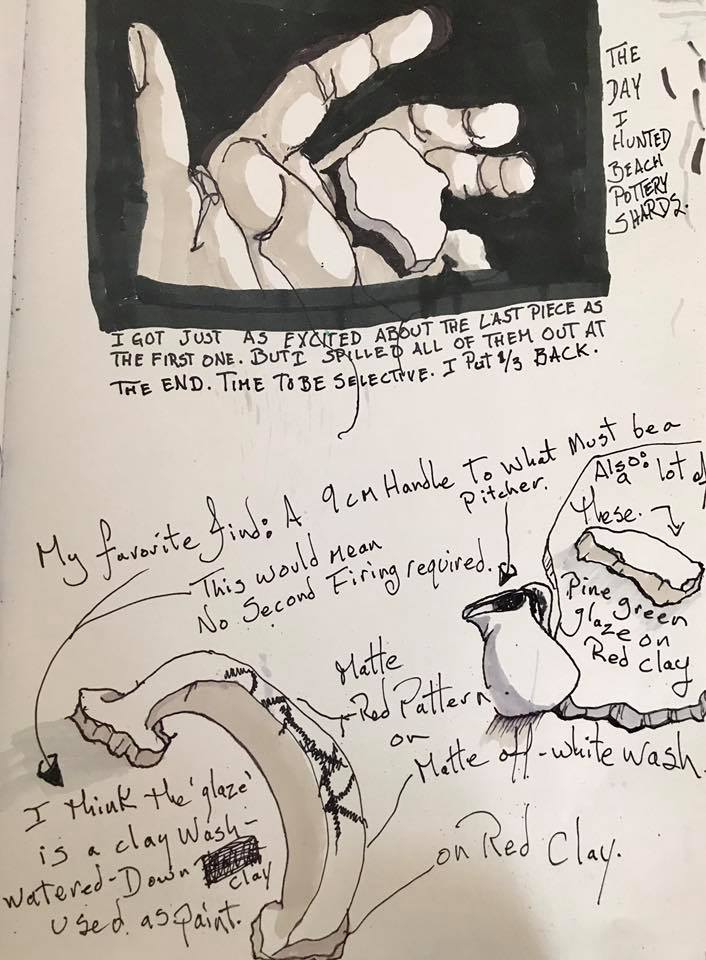

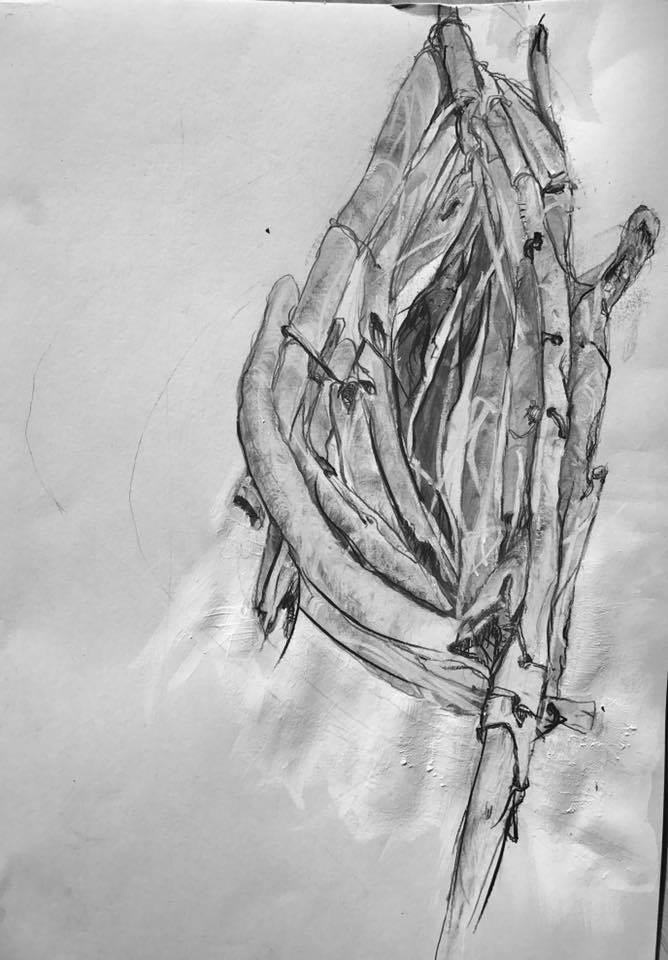

Every one of the hundreds of gray wood pieces in this installation I bleached in the sun, painted with ink wash, then burnished by hand. It took hundreds of hours over three months. The resulting surfaces are iridescent; the light enters the first layer and reverberates underneath. The sticks making up the hanging boats went through the same process, only without the ink, distinguishing them from the riverbed. For the boats I carefully selected driftwood that had the knobby appearrance of sun bleached bones, and after burnishing the bleached wood, drilled holes and threaded them with copper wire. Although porous, they do float. One of the boats conceals a small LCD projector pointing downwards upon salt and white pottery shards. I collected all the pottery shards from the riverbanks. I checked with the local museum; who not only dated them from the previous century during which all this history took place, but centuries before that as well, including a few dark clay pieces, incised and burnished without glaze, probably from Roman times. The looping black and white video shows the installation’s boats floating and bumping together in the real Danube. The English, Slovak and Hungarian text rubbings come from the bridge itself. There a poem by the Hungarian poet Fereck Kölcsey is carved into the foundation of the bridge. It concludes, “Gather the ruins and build a strong base for future greatness. Make the works of peace plentiful.” Eerily, I did not find this poem until the week before the show, even though it reads as a recipe for this work.

It would have been impossible to save this whole installation and bring it home. I left one boat with the residency, packed one giant suitcase with the other boats and my favorite sticks. The rest I surreptitiously bundled and stored in the unfinished residency basement, suspended off the floor so it wouldn’t get wet. Maybe one day I can re-assemble the show, and if not, it will be a curious discovery for someone.

the DNA curves of both the pottery shards and driftwood lines overlap each other.

Three handmade boats were suspended above the ‘river’, while the fourth was dissolving’ into the river

Each of the thousands of sticks were bleached, painted with ink, and hand burnished to a high sheen.

Copper wire is threaded through drilled holes to hold together bone-like driftwood with gilded wounds.

Documentary drawing of one of the boat elements from the installation.